In this article on acclimatisation and altitude sickness we have provided general information on acclimatisation and a full outline on altitude sickness, HACE and HAPE, as well as set out best practice information on preventative medications like Diamox.

At the end of this page we have included some useful information on travel and trekking insurance, which we highly recommend you obtaining prior to trekking or climbing abroad.

We have used a variety of guides and resources to write this article. In particular, Rick Curtis’ Outdoor Action Guide to High Altitude, which was written for Princeton University, and research from the Everest Base Camp Medical Centre.

This guide is particularly useful for hikers looking to climb Kilimanjaro, hike the Inca Trail or trek in Nepal on famous hikes like the Everest B.C. trek or in the Annapurna region.

This article contains affiliate links. It won't cost you extra, but if you buy something using our links, it will help us keep the site alive!

Disclaimer: The information on this page is provided as an information resource only, and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes.

The information is not intended to be patient education, does not create any patient-physician relationship, and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment.

The team at Mountain IQ have worked hard to provide the most up to date information on altitude sickness, however, research in this area is always progressing which may mean some of this information is out of date. It is your responsibility to seek the latest information should you be going to high altitude.

Altitude Sickness - The Basics

Acclimatisation Explained

Acclimatisation is a process that results in the body becoming accustomed to lower levels of oxygen at altitude. It is only achieved by spending extended periods of time at various levels of altitude before progressing higher.

Climbers typically refer to three main levels of altitude. The first level, aptly called ‘high altitude’, describes the altitude zone between 2,500m and 3,500m. Altitudes between 3,500m and 5,500m are referred to as ‘very high altitude’. The third level is called ‘extreme altitude’ and is characterised by zones above 5,500m. There are other zones above extreme altitude, but these are limited to the highest mountains in the Himalayas – like the ‘death zone’ which is above 8,000m!

When it comes to trekking at altitude, most people can ascend from sea level (say your hometown) to 2,400m without experiencing altitude illness symptoms. Once you get beyond this height though, changes in oxygen and pressure levels begin influencing the body’s physiology.

To illustrate these changes consider the following.

At sea level oxygen air saturation is about 21 per cent and barometric pressure is approximately 760mmHg (millimetres of mercury). As one ascends oxygen saturation stays about the same but air density decreases, which means the percentage of oxygen per breath reduces. You can imagine this as oxygen molecules moving further and further away from each other at higher altitudes, hence the term ‘thin air’.

The good news is that as oxygen per breath decreases, the body very quickly and cleverly starts to adapt to the new environment.

Four main changes occur.

- Breathing becomes a lot faster and deeper (even at rest).

- Blood concentration changes – red blood cells, the part of your blood responsible for carrying oxygen, increases.

- The third change occurs in your lungs and is a result of increased pressure in your pulmonary capillaries. This forces blood into areas of the lungs that are not used when breathing at sea level.

- The final change involves the secretion of an enzyme that promotes more effective transfer of oxygen from your haemoglobin to your blood tissue.

With these changes and, assuming you have given yourself enough time to rest at a ‘reasonable’ starting altitude, the body will acclimatise. Progressing to higher altitudes on a slow and incremental scale thus becomes possible.

Acclimatisation Line

To demonstrate acclimatisation in action, trekkers and mountaineers have come up with a term called the acclimatisation line – an arbitrary altitude line that describes the point at which someone’s altitude sickness symptoms appear.

For instance, let’s assume that your altitude line is around 3,000m. On the first day of your trek you ascend to 3,000m and remain asymptomatic as you are on or just below your acclimatisation line.

Resting at this altitude for a night or two should ensure that you are fully acclimatised to this altitude and your line might move to around 3,800m.

Trekking to 3,700m will ensure you remain asymptomatic, but if you continued further to say, 4,000m, it is likely that you will start experiencing altitude illness symptoms.

Descent back down to below your acclimatisation line (in this example, 3,800m) to rest for a few days should resolve any symptoms. Continued ascent would only result in the deterioration of your condition.

So what is the learning?

If you want to acclimatise properly make sure you build in rest days as you ascend, make sure to take note of your altitude if symptoms present themselves.

Near your acclimatisation line altitude sickness symptoms typically resolve after a day or two, but continued ascent before you have properly acclimatised will almost certainly lead to the worsening of your symptoms and further acclimatisation will not occur.

The only sure way to improve is to get below the altitude line where your symptoms first occurred.

Altitude Sickness - Symptoms

Altitude illness (aka Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) or altitude sickness), is a condition caused by fast ascents to high altitudes. Susceptibility to altitude sickness increases for most people at around 3,000m, some can experience altitude illness symptoms as low as 2,400m.

There is little in the way of identifying whether you are susceptible to altitude sickness as there is no correlation between age, fitness, health, gender, or indeed previous experiences of going to high altitude. What we are sure about is that climbing more than 500m a day from 2,400m increases the probability of altitude illness; exerting yourself at high altitude and dehydration also exacerbates symptoms.

In general, symptoms of altitude illness fall into three categories – mild, moderate and severe. Typically one moves from mild to more acute symptoms as the condition worsens.

That is to say that there are usually early warning signals that you are suffering from altitude illness and that your condition is getting worse. Severe variants of altitude sickness, like HACE and HAPE, can occur as one’s condition deteriorates. Transition to these severe conditions is often very rapid!

- Moderate Symptoms

- Severe symptoms

Mild altitude sickness symptoms include:

- headaches

- fatigue

- lost appetite and nausea

- shortness of breath

- dizziness

- disturbed sleep

Symptoms of mild altitude sickness typically present between 12-24 hours after arriving at altitude and are common for trekkers in mountain regions.

Resting for 24-48 hours at the altitude at which mild altitude sickness presents often resolves symptoms. Once symptoms have subsided at the altitude they begun, you can conclude that you have acclimatised to that altitude.

Lake Louise Scorecard

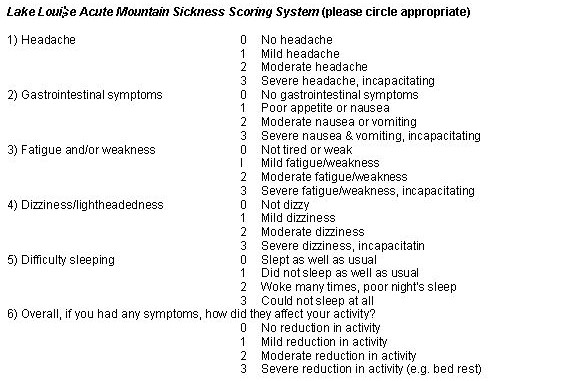

The Lake Louise altitude sickness system is the most common way to test how bad your altitude illness symptoms are. A score between three and six is a sign of mild to moderate altitude sickness, scores over six indicate severe altitude sickness.

High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema (HAPE)

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) is another fatal altitude illness condition. It occurs when fluid breaches the pulmonary capillaries and enters the lungs. Fluid in the lungs inhibits the effective exchange of oxygen to the blood.

Here are the signs that someone is suffering from HAPE: very tight chest and extreme shortness of breath (even while resting), the feeling of suffocating, particularly during sleep, coughing up white or mucus coloured frothy fluid, extreme fatigue, irrational behaviour and hallucinations.

Like HACE, descent is paramount, but caution should be taken not to exert the person suffering from HAPE as this can worsen the condition. Any available oxygen can and should be administered. The drug, Nifedipine, has also been shown to help ameliorate the condition, but descent is the only

High Altitude Cerebral Oedema (HACE)

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) is a severe altitude sickness condition. It occurs when pressure build-up in the brain results in fluid breaching the capillary walls in the cranium. It is a rare condition on general treks, but much more common among mountaineers in high altitude mountain ranges such as the Himalayas.

Here are the typical symptoms for suffers of HACE: very bad migraines, loss of coordination, hallucination and disorientation, memory loss, and loss of consciousness (ultimately leading to lapsing into a como). Generally HACE tends to strike at night and the condition can worsen rapidly. Hence, time shouldn’t be lost in getting someone down to lower altitudes if they have suspected HACE. Do not wait for daylight. Descend immediately.

Oxygen can be administered along with a steroid called Dexamethasone, However, these should only be used in tandem with fast descent.

Golden Rules To Avoid AMS

The purpose of going through the symptoms of altitude sickness above is not to scare you but rather to enlighten you of the potential conditions so that you can avoid them. It is important to remember that severe altitude illness and HACE and HAPE are rare on treks. Only a few treks in the world go to extreme altitude (above 5,500m) and in general all routes in the country have good altitude profiles that allow for good descents after going over high passes.

Below we have set out a a number of golden rules to remember:

- If you feel sick at altitude, assume it is altitude illness until proven otherwise

- If you are suffering from altitude illness symptoms do not ascend further

- Get over high passes / summit climbs quickly and then descend

- If symptoms continue to worsen after resting at a certain altitude, continue to descend immediately

Additional Tips To Follow

- On your trek make sure to build in acclimatisation days where you relax and drink lots of fluids

- Ensure you remain very well hydrated on the trail – drink two to three litres of water a day

- Go slowly and don’t over-exert yourself

- Avoid alcohol, smoking and stimulants whilst trekking (although there is some evidence that suggest caffeine can help with acclimatisation)

- Work with a respectable operator or guide who understands the risks of altitude illness and is trained / has the equipment to deal with any potential problems

- Try to ascend in small increments of 500 meters a day, this can include trekking high (say 700m up) to sleep low (500m from the start point from that day)

- Consider taking a preventative medication like Acetazolamide (Diamox) as an extra precaution – see below

Prescribed Medication – Diamox

Diamox, clinically known as Acetazolamide, is a prescription drug that effectively helps mitigate altitude illness. It is a preventative medication (aka a prophylactic), and not a cure. This means that it helps with promoting faster acclimatisation and thus prevents the potential onset of altitude illness, but does not cure it.

Depending on where you live in the world you may need to get a doctor’s prescription, but more often than not it can be bought over the counter at a pharmacy. We recommend you consult your doctor before using it. The drug should not be taken by pregnant women or people with kidney and liver issues.

Side effects of the drug include frequent urination; taste alterations; numbness and tingling in toes, finger and nose; and drowsiness, nausea and vomiting. Many of these side effects can be misdiagnosed as altitude illness. To avoid confusion we recommended that you take a short dose of Diamox a few weeks before departing for your trek to test if you experience any side effects.

Diamox is usually sold in a 250g tablet. Most hikers take 125g in the morning and the remaining 125g in the evening, starting one day before starting a trek and finishing on the day one returns to the trek start point.

In our opinion we think it is worthwhile taking Diamox as a preventative measure if you plan to do a trek that goes above 5,000m but recommend consulting your doctor before you do so.

Travel & Trekking Insurance

As you are already aware, high altitude hiking comes with obvious risks. We recommend that you get adequate travel and trekking insurance for your adventure. The trouble is that most generic travel policies are in fact inadequate when interrogated properly as they do not offer cover for trekking at altitudes over 2,000 meters.

To help you decide which policy is ideal for your high altitude trek please read our detailed article on trekking insurance.

FAQ

If you have any further queries about acclimatisation and altitude sickness, or if you would like to provide some feedback on this article, please contact us.

Tags: Acclimatisation and altitude sickness, Nepal acclimatisation, Himalaya acclimatization, Nepal Diamox, Diamox Everest Base Camp trek, altitude sickness Everest Base Camp trek, altitude sickness Annapurna Circuit

See more hiking resources.

References: (1) Altitude Org (2) NHS (3) Wikipedia

He failed to explain in a simple straight forward manner what actually happens. I'm willing to re-do the video.

Mark, good column, thanks. I have a question. Climbed Kili in June and am still trying to sort if my symptoms up and down from High Camp were altitude sickness or something else. 1)I drank 2.5l of water going up and 1.5l coming down, half with electrolyte, and had no desire to urinate until well after down hours later. I normally flow easily. 2)I had no problem staying with the group, but my mind became very narrow, only able to focus on stepping, keeping warm, drinking, eating; just the essentials. This lasted roughly from the top to several hours after, down below 16K.

Anyway, my first idea was that I just ran short of calories, but I ate a bunch of jerky and clif bars and gorp and gu on the way up and down, so I am not convinced. But I never read about my symptoms as possible parts of altitude sickness. Took Diamox daily from the gate, 62 year old male, made it up Lemosho to High Camp easily, then had these odd things just on final ascent. Does this sound like altitude, or more like calorie deficit? Thanks.

Hi David, your symptoms were almost certainly altitude sickness and not something else. Altitude sickness can come on quite quickly. Symptoms vary, but from what you describe in terms of a narrowing of the mind, sounds like classic altitude sickness symptoms. Obviously, fatigue and nutrition would also be contributing factors, but I would say altitude is the primary factor. Hope this helps.

Mark, thanks for the feedback. It does help me make sense of it. Have you heard of lack of urination as part of altitude sickness? Or should I attribute that to a hard hike in a dry and cold environment (like if it were dry/hot instead)? Finally, I became oddly emotional at the top. Have you seen this linked to altitude? A singular experience despite it all. David

Hi David, it’s usually the opposite – one urinates more often as the body works to avoid respiratory alkalosis (elevated blood PH) by your kidneys excretion of bicarbonate. Not sure whether the emotional state you experienced was due to altitude sickness but it’s possible.

I am 70 years old and had a coronary bypass surgery six years ago. Since then generally I have been in good health

Is it advisable for me to visit Lhasa in Tibet? Thanks.

Hi Sathis, thanks for getting in touch. Unfortunately I’m not qualified to answer that question. I recommend consulting your doctor to get the all clear before travelling. All the best!

I am 79, and have a damaged lung and mild asthma. Should I go to Santa Fe (7,000 feet)?

Hi Nigel, thanks for getting in touch. Unfortunately, I’m not qualified to answer that question. I recommend consulting your doctor. All the best!